Exercise, clean air, adventure and a healthy dose of Vitamin D from the sun for musculo-skeletal wellbeing are givens. In recent years medical research has even revealed that microbes in plants, soil and fungi are beneficial to our immune system’s development and health. In short, the physical benefits are well-known and being increasingly well-documented.

What is less well known however are the links between nature and mental health. Take cortisol – a hormone linked with stress that decreases dramatically when people spend time outdoors. We now know this response is genetically inbuilt, making sense when you consider that humans have spent 99 per cent of our evolutionary history living in nature as hunter-gatherers. Basically, (with the exception of First Nations peoples who’ve always retained this deeper connection), it’s only in the last few thousand years out of the 400,000 that humans have been around that we’ve been living in structured, urbanised environments that, turns out, aren’t that good for us.

Two researchers, Orians and Heerwargen published a study in 1992 called ‘Evolved responses to landscapes’. They outline the ‘savanna hypothesis’, which describes the wonderful idea that the innate need to be in nature is driven by the evolutionary ‘ghost’ of that savannah environment we evolved from in our brains.

That trip you take to K.I. is in fact part of a deep-seated need to reconnect with your evolutionary past!

Put another way, from an evolutionary perspective, humanity’s ancestors spent so long in the African savannah that it’s part of who we are. We need those natural environments to give us a sense of mental calm. We aren’t properly equipped to manage the levels of overstimulation we subject ourselves to in city scapes.

And this was echoed by environmental psychologists – Rachel and Stephen Kaplan in the 1980s. ‘Attention restoration theory‘ argues that natural environments – pure, unthreatening landscapes – are something we can pay ‘indirect attention’ to. This form of attention, in turn, has a soothing effect on the brain.

If you think of the wonderful natural environments of South Australia, for the most part they’re peaceful and harmonious – you don’t need to devote a lot of mental energy to them when you’re in them. In the urban world however, our brain needs to work incredibly hard to process all the stimuli we’re surrounded with. Evolutionarily speaking, this isn’t a good thing – because our brains are designed to constantly search for danger. Our natural state is to be using indirect attention, absorbing the environment around us.

And it’s not just nature out there that benefits you mentally but links between the health of your gut microbes and how they interact with neurotransmitters like serotonin in our brains that are crucial in regulating our moods and emotions. Put another way, the more natural the foods you eat, and the more time you spend in nature exposing your gut biome to microbes that improve its health, the better your mental health is likely to be.

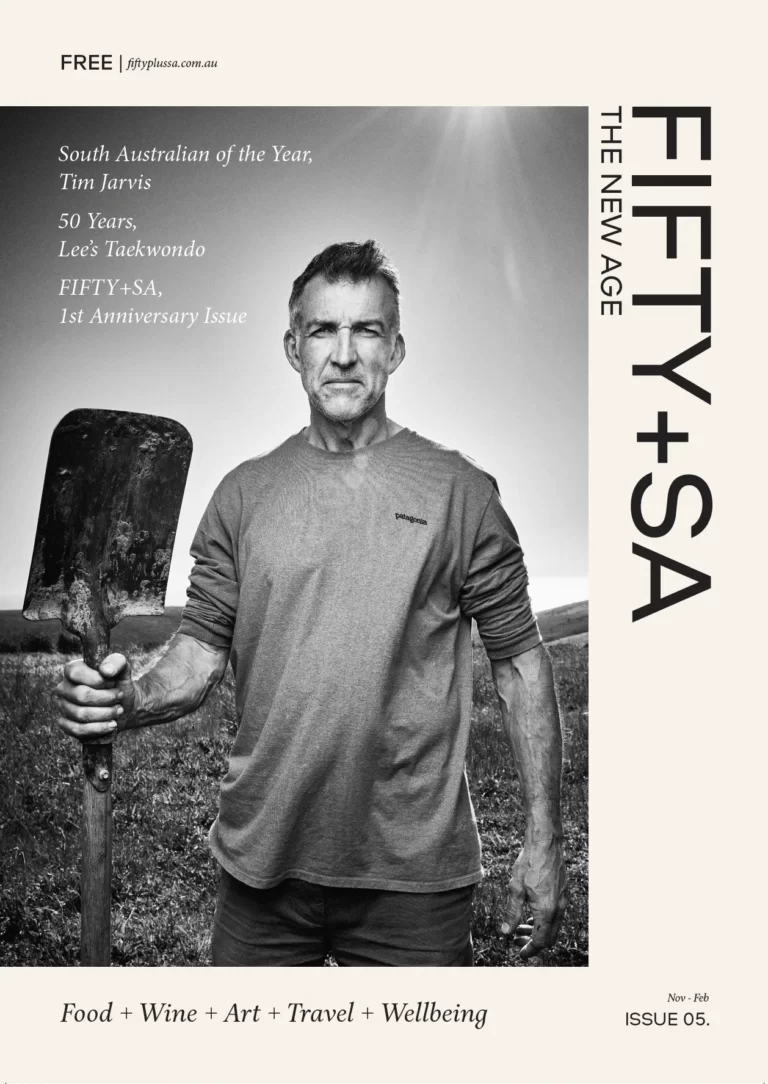

Someone like me spends a lot of time planting trees and pulling weeds, repetitive tasks in a natural space, and these can also have surprising mental upsides in that they allow a deeper cycle of thinking to happen whilst our brain is engaged in simple repetitive tasks.

We all understand that a computer needs a bit of time to process complex information – yet we don’t apply this logic to ourselves. We’ve got the most effective supercomputer ever created sitting between our ears but perhaps don’t give it sufficient time to process information and ‘back up’ and nature is a great place in which to do this.

Finally, amongst all the bad news we hear about crises like climate change and the decline of nature is the importance of controlling what you can and what this means for your personal mental health. This means doing something about your own circumstances, regardless of what others are or aren’t doing. Like school kids planting a tree when they come on a visit to a restoration project like Forktree – a sense of control and wellbeing, having done their bit regardless of the bigger picture.

Each year in Australia, about a million people will experience depression, and another two million will experience anxiety. There’s demonstrated evidence that access to natural environments can, in part, alleviate some of this mental health burden. And if we can’t bring people to green spaces, we need to bring these spaces to them, something South Australia is leading in with initiatives such as Adelaide becoming a National Park City – a movement to improve liveability in Greater Adelaide by connecting people with nature through everyday actions.

Ten years ago I was involved in a study carried out by global engineering firm Arup ‘Cities Alive – Designing for Urban Childhoods’ that talked about the need to design cities for kids. There’s an elegance to this approach. Children can’t drive cars: in a city for kids, you need to travel from point A to point B by bicycle or foot without crossing busy roads. It’s a good philosophy as a city designed in this way will prioritise shared natural spaces that are accessible without the need for people to actively seek them out.

At the end of the day we’re kidding ourselves if we think we’re separate or distinct from the natural world. Just because we can build environments removed from nature, we can’t escape the need for it. First Nations Australians know it and we should listen to their insights. If we do, nature might just save us from ourselves.

For more information: