What is endometriosis?

The condition is characterised by tissue typically found inside the uterus, growing abnormally outside the uterus, causing inflammation and scarring in the pelvic region. The pain it causes commonly disrupts the work, social and sex lives of women and can be so excruciating that some find it very difficult to function in their daily lives. It’s also associated with high rates of infertility.

Endometriosis can start from the first menstrual period and last until menopause. The symptoms typically include severe pain, bloating, nausea, fatigue and it can also be linked to depression and anxiety.

The disease is often left to grow and do more damage, as it takes an average of seven years to diagnose. This is due to the symptoms often being wrongly attributed to a range of other common health issues.

There’s currently no cure for endometriosis and treatment is aimed at controlling symptoms, with surgery being the primary method of providing relief. Access to early diagnosis and effective therapy is crucial to minimising chronic pain and preventing infertility.

The research

SAHMRI’s Visceral Pain Research Group is determined to find more successful and less invasive treatments for endometriosis, with the goal to empower those living with it by supporting their human right to the highest standard of sexual and reproductive health, quality of life and overall well being.

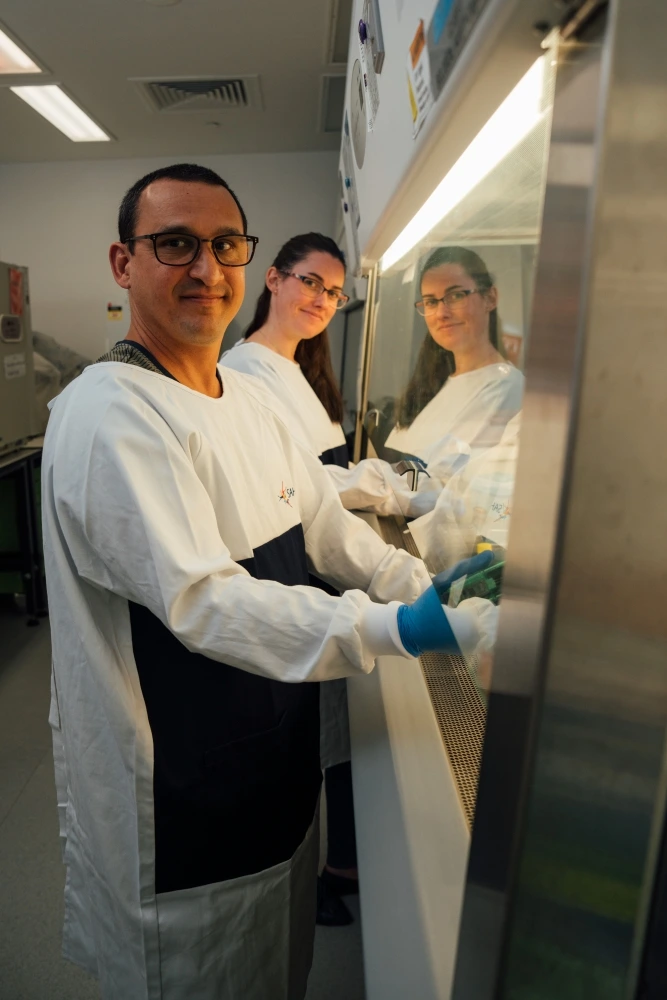

Research Assistant, Dr Jess Maddern spends her days working to discover answers for endometriosis, which has plagued her since she was a child.

Our team has identified specific changes that occur in the nerves and tissue in endometriosis patients and we’re targeting the cause of these changes to block the pain experienced in endometriosis.

Jess’ story

Before I turned 13, I was already experiencing the symptoms of endometriosis.

As soon as I got my first period, I started having chronic pelvic pain that rarely left me. I was taken on constant trips to the doctor and was made to think I was weak and just couldn’t handle pain like other people can. It got to the point where I was having injections every month to try to cope with it and I was only a child. Fortunately, my mum kept pushing and taking me to different doctors until I got a diagnosis.

Endometriosis research is close to my heart, as someone who not only suffers from the condition, but also has friends and family who live with chronic pain associated with this disease.

I was put on hormonal birth control to manage the symptoms and told it was unlikely I’d be able to have children. That was a lot to take on as a young person. Fortunately, it proved not to be the case and much later in life I gave birth to my son William and daughter Charlotte. However, after having children the pain escalated quickly and birth control pills no longer had an effect. I had to make a difficult decision, choosing to undergo invasive surgery that has left me infertile, to relieve the pain.

Endometriosis research is close to my heart, as someone who not only suffers from the condition, but also has friends and family who live with chronic pain associated with this disease. My journey from being a patient to becoming a researcher has given me a unique perspective that I now apply to my work.

It’s always been my goal to do a PhD and having the opportunity to do it on endometriosis has been so important to me. During the years I’ve been completing my thesis, our team has identified specific changes that occur in the nerves and tissue in endometriosis patients and we’re targeting the cause of these changes to block the pain experienced in endometriosis. Through our preclinical studies, we’ve tested a specific drug that had already been trialled in people with cancer and found that it reduced pain. We’re optimistic about taking this forward to clinical trials.

We’ve learnt so much from other conditions that we can apply to endometriosis and we’re now in a position where we’ve got the momentum and the capability to make great progress in the next five to ten years. But we’re still decades behind so many other well-known diseases like cancer, so it’s crucial that we keep endometriosis front of mind to help garner the support needed to power more research, because we want to get these women the help they need as soon as possible.

Despite the challenges ahead, I’m confident that with the community’s help, we’ll get to a point where we can drastically reduce the damage and discomfort caused by this disease. Dr Maddern works alongside Dr Joel Castro, another SAHMRI researcher for whom the quest to end endometriosis is personal.

I want to help my sisters and all the women suffering from endometriosis; we can’t ignore the significance of this major health problem and just accept that millions of women must live in constant pain.

Joel’s story

I was born and raised in Cuba, where I was given the freedom to spend much of my childhood going on adventures and discovering the world for myself. From a young age, I was curious to find out how things worked and it was my inquisitive nature that eventually led me to research. I was always particularly interested in the biology of living things, how we function, what happens when something goes wrong and how it can be fixed.

After finishing my bachelor’s degree in Microbiology at the University of Havana in 2000, I migrated to Chile and found a job as a research assistant, investigating cellular processes involved in cell death. This was a totally new area for me and had little to do with my original studies, but I had great colleagues, so I worked hard and challenged myself to stay with it. This led me to apply for an Australian government scholarship and came to Adelaide to do a PhD in 2005. After finishing my PhD, I met my current supervisor, Professor Stuart Brierley and ended up working in his visceral pain lab at SAHMRI.

We still have a long way to go, but we’re making great strides towards a better future for women living with this condition and with enough support I truly believe we can bring an end to endometriosis.

Finding a cure for endometriosis is my main goal and it’s a mission that’s very close to my heart. Both of my sisters have suffered from endometriosis from a young age and it’s been terrible to see them endure such pain and not be able to do anything to stop it. I still have a vivid memory of my older sister curled up in bed and not wanting to go to school or out with her friends because she was in so much distress.

I want to help my sisters and all the women suffering from endometriosis; we can’t ignore the significance of this major health problem and just accept that millions of women must live in constant pain.

Trying to find answers to such difficult questions keeps my mind ticking over and challenges me to continue developing new ideas. Most importantly, it gives me the opportunity to do something with that knowledge that could contribute to changing the world for the better.

My research really centres on understanding why exactly people who suffer from disorders such as endometriosis and irritable bowel syndrome, experience chronic visceral pain. So far, we know that our internal organs are infiltrated by nerve fibres that send information to the brain, signalling what’s going on in the body at any given time. Inflammatory disorders trigger these nerves to send abnormal information, which the brain perceives as pain. What we don’t understand is why this happens and how to stop it. If we’re able to first make sense of exactly how these sensory nerve fibres are malfunctioning, that’ll open the door to rectifying the problem and quelling the symptoms.

Current treatment options for endometriosis are limited to hormonal suppression of ovarian function, using a contraceptive pill or surgical removal of endometriotic lesions that grow on pelvic organs. Unfortunately, these treatments are invasive, have varying success and can lead to infertility. We’re focused on identifying the mechanisms that cause sensory nerves to develop abnormal sensations in endometriosis. This knowledge will allow us to target the first step in the pain pathway and either create a new drug or repurpose one that already exists for another purpose, that can offer significant relief without the detrimental side effects like those caused by opioids. We still have a long way to go, but we’re making great strides towards a better future for women living with this condition and with enough support I truly believe we can bring an end to endometriosis.

If you’d like to contribute to Jess and Joel’s mission to find new treatments for endometriosis, please donate to SAHMRI’s endometriosis painkiller appeal.

SAHMRI

sahmri.au/painkiller

sahmri.org.au