WORDS: Dr Kiera Lindsey, South Australia’s History Advocate

I have spent much of my life wondering about women and their place in the past. Having been brought up on stories of pioneers and politicians, I imagined the nineteenth-century world as a place inhabited by horse-galloping bushmen and top-hatted gentlemen where women wore bonnets and stayed at home making butter. I spent much of my childhood chafing against the limited future awaiting me, for I feared I had little chance of making my mark.

When I became a historian, I was relieved to discover there had always been strong women. At the same time, I was shocked by the extent to which women had been obscured from the historical record. Not only were women often denied the education to read and write, but few could afford paper and pen. Even when a woman produced a written document these were rarely deemed worthy of preservation. Most of the women who have made it into history, have done so because they got into the sort of trouble that landed them in newspapers, courts and institutions, where their stories were told by male police, legal authorities and reporters.

Our history is skewed in ways which impact upon us all because we need to see ourselves as active agents in the past if we are to take control of our lives in the present and inspire future generations to do the same. To address this imbalance, I seek to ‘re-present’ little-known women by pouring over every surviving snippet and learning all I can – from the sort of boots she might have worn to how her life was shaped by the big ideas of her age. Such intimate portraits always reveal a different past to what we see from looking through official sources.

Take, for example, these four fabulous South Australian women.

The first is almost certainly wearing a bonnet as it is a hot day in late 1836. She is twenty-five years old and, if one of few surviving sketches thought to be of her at Rapid Bay is accurate, she has a long nose and striking face. Hopefully, both are shielded from the sun as she stands on deck beside her partner and two younger brothers. The wooden brig is making its way down Yerta Bulti, the tidal estuary which the Kaurna call ‘the land of sleep or death’, and as she is the first European woman to travel through these parts, she is taking in the mangroves, seagrass and waterbirds carefully. Perhaps dolphins slip through the silvery stream as Kaurna gather kakirra, black river mussels, from what will soon become known as Port Adelaide River.

Thanks to the excellent work of Isabel Story at the State Library, we now know Maria Gandy, our woman in the bonnet, was of humble working-class stock. She probably met Colonel William Light in the early 1830s when he returned to London from Egypt, hoping to be appointed Governor of the colony of South Australia. At the time, Light was fleeing a disastrous second marriage to the beautiful Mary Bennett, but as she had taken most of his money before leaving him for another man, he was in no position to pay for an expensive divorce. Maria became Light’s housekeeper in England, however, by the time the pair set sail for the new colony, those on board the Rapid considered her the Colonel’s companion.

Maria supported South Australia’s first Surveyor General as the bitter political dispute associated with the location of Adelaide took its toll upon his uneven health. She was by his side when their hut burnt down and they lost all their possessions ‘but the clothes they were wearing’, accompanying Light into town to buy household utensils. All the while Maria suffered severe social ostracism from the respectable citizens of the new colony who condemned her as Light’s concubine. Then, in 1839 she endured the intense physical and emotional demands associated with caring for the Colonel as he succumbed to consumption. Such devotion probably explains why he made her the executrix of his will. With this inheritance, Maria Gandy then made a respectable match with Dr George Mayo, with whom she had four children, three of whom survived her, when she died of consumption in December 1847.

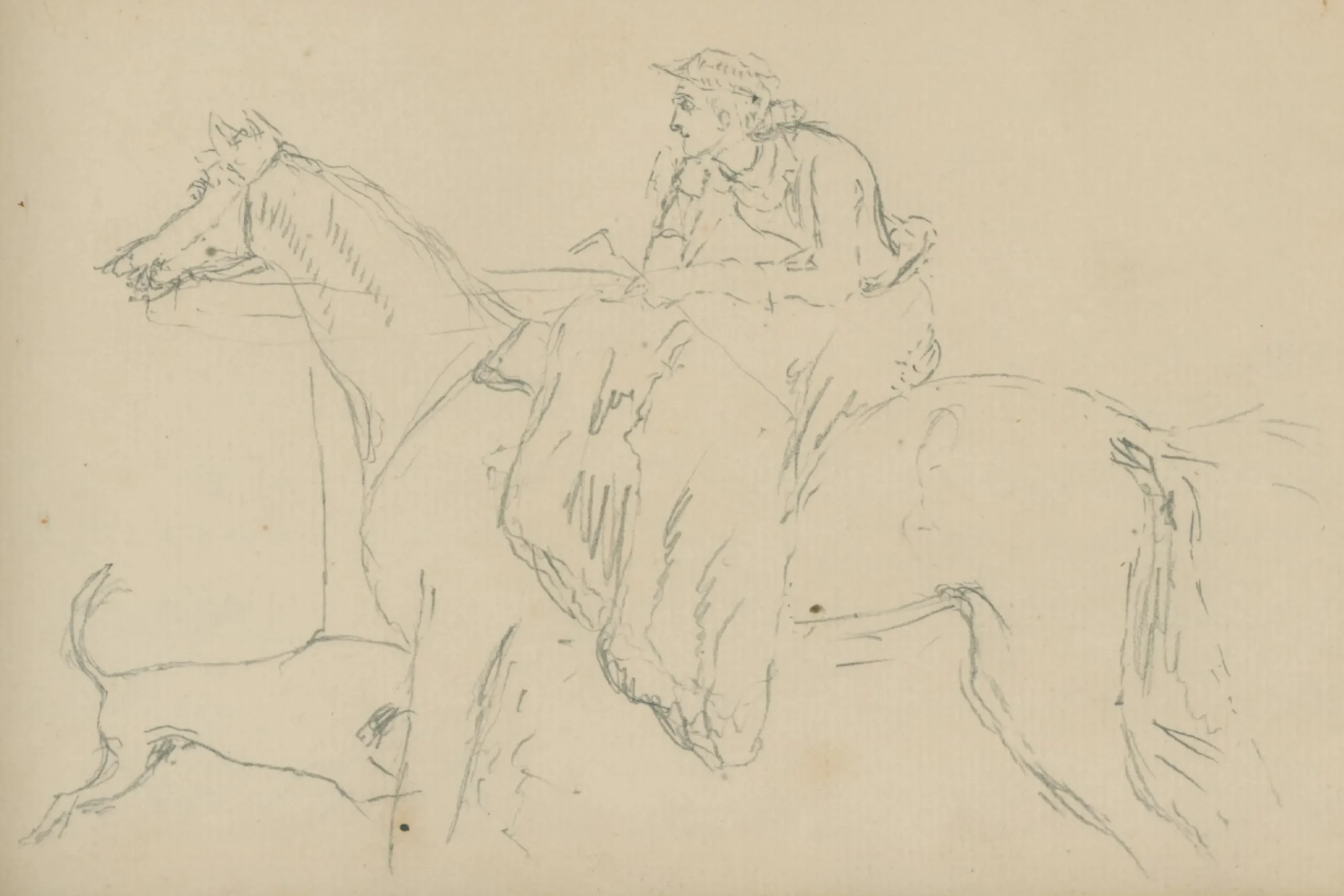

This unfinished sketch by Colonel Light of an unnamed woman sitting side-saddle, chin resting on one hand and crop in the other, may be one of the few historical remains relating to Maria Gandy. Other than the legacy of her children and her grandchildren, that is, for her descendants include medical doctor and educator, Helen Mayo, who co-founded the School for Mothers in 1909, and the ‘Mothers and Babies Health Association’ in 1927. In 1935, almost a century after her grandmother arrived in South Australia, Helen Mayo was awarded an OBE, something that would have astounded the respectable colonists who refused to visit the Colonel and his ‘concubine’ at their Thebarton Cottage. According to the Australian Dictionary of Biography, Helen Mayo was:

‘ … a progressive woman of forceful views. … She was short and plump with curly hair, a round face and alert expression with a deep rich voice and infectious laugh. She preferred ‘sensible English clothes’ and had a brisk and bustling manner … Unmarried, she shared a North Adelaide house with her partner Dr Constance Finlayson’.

While our first nineteenth-century heroine comes to us in a bonnet, our second was not wearing one the day she married Thomas Adams, an English shepherd, in Adelaide, 27 January 1848, less than two months after Maria Gandy’s death. We know this because the press were so intrigued by the occasion that they attended the ceremony when Kudnarto, a sixteen year-old Kaurna-Ngadjeri woman, become the first Aboriginal woman to marry a European in South Australia. Their reports reveal Kudnarto wore her hair ‘carefully dressed’, while her ‘pleasing expression’ convinced them her groom was ‘a lucky swain indeed’.

Thanks to her marriage, Kudnarto become the first Aboriginal woman to be granted Aboriginal reserve land, which she did according to South Australian legislation which gave an Aboriginal woman and her children the right to occupy the land – although a clause denied her husband from doing so if his wife died. The Adams Family took up 81 acres in the Clare Valley, where Kudnato gave birth to her two sons.

Despite the law including a provision for the land to go to Kudnarto’s children, when she ‘died suddenly’ in February 1855, the government reclaimed Section 346. Unable to care for his children, Adams took his sons to Poonindie Mission near Port Lincoln where they became excellent shearers and cricket players and eventually raised large families of their own. Like Maria Gandy, Kudnarto’s legacy can be traced through her descendants who include many prominent Kaurna figures including Uncle Lewis O’Brien and AFL player, Michael O’Loughlin, although I would like to focus on Kudnarto’s great, great grand-daughter Gladys Elphick.

Trained as a midwife according to traditional ways, Gladys eventually became active in the Aboriginal Advancement League of SA before establishing the Council of Aboriginal Women of SA, where she set up a women’s shelter, health service, a legal aid service and kindergarten. In 1971 `Aunty Glad’, as she was known to many, received a Member of the Order of the British Empire and remains greatly admired for her many achievements as well as her `lively sense of humour’ and `shrewd personality’ which pierced through `humbug’.

Together, these four fabulous South Australian women invite us to consider what we will leave behind and how we might be remembered. I like to think that Maria Gandy’s influence can be traced to Helen Mayo – and not only through her achievements but also that infectious laugh. Likewise, that Aunty Glad’s `lively sense of humour’ and `shrewd personality’, reveals something of Kudnarto, the Kaurna-Ngadjeri woman who proves that it’s possible to exercise agency whatever the circumstances, with or without a bonnet.

Hero image: Thought to be Maria Gandy from William Light’s Survey field book, 1818-1837. SLSA: PRG 1/4/177/173